In our culture, many people, especially those raised male, have been given little training in making sense of or talking about their internal experience. Indeed, many were actively punished for showing emotions or expressing uncertainty, doubt etc. Shamed for their normal, human vulnerabilities they have understandably developed an aversion to talking about their feelings and deeper meanings. I often will say, only half-jokingly, that the only emotions a man is allowed to express are anger and lust. In many relationships, all negative emotions are channelled into anger, aggression, irritation and frustration. All positive and affiliative impulses are channelled into requests for sex.

Having a person like this as your client can be challenging. Enquiries about their emotions or the meanings they make of events are often met with an “I don’t know” response. Many of us were trained never to lead clients. If we are rigid about this it can leave us with few options at this point. However, there is a real danger in the client remaining unseen and unheard. If you are doing couple therapy there is also the danger of partners losing hope “See, even our therapist can’t get anything out of you!”

If you suspect your client DOES know but isn’t saying you can enquire about that. You can ask “Is that an “I know but it’s too scary to tell you” type of “I don’t know” or an “I have no idea how to process what you are asking me” type of “I don’t know”?”. If the answer is “too scary” then that opens up an avenue of exploring what are the feared outcomes of answering the question.

If the person doesn’t know how to process the question, consider what you know from their history about how likely they were to have been taught or have modelled for them how to think about nor talk about their emotions and internal experience. In most cases, they haven’t had the training, and so our role becomes to scaffold them up to the kind of emotional literacy needed to maintain an intimate adult relationship.

In a sense, our role becomes one of re-parenting. It requires patience and compassion from the therapist. It is so easy for these men to feel inadequate and ashamed. In many cases, they have had years of partners expressing frustration at their inability to be open and articulate. Therapy is a very scary and hostile environment for them and it is our professional responsibility not to add to the emotional burden they carry.

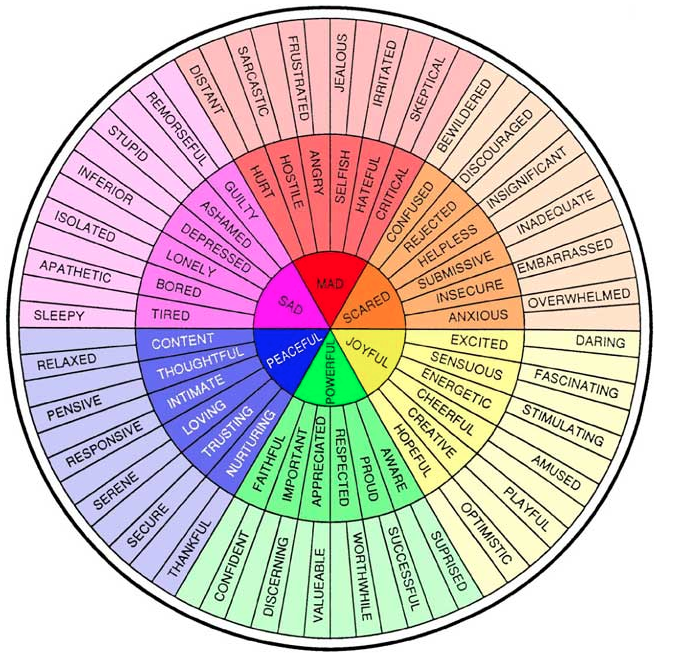

One tool to use is to use the Feelings Wheel – I focus on the 6 core emotions in the centre. Although I acknowledge that there is a downside to labelling emotions as positive or negative (all feelings carry useful information), at this level of education I find it valuable. In response to an “I don’t know how I feel” I ask, “Well, do you feel negative or positive?” Most people can answer this kind of simple binary question. Armed with this knowledge I get out the Feeling Wheel. Using the wheel they then only have to choose between 3 options. If they say it’s a negative feeling – is it Sad, Mad (angry) or Scared? If it’s a positive feeling, is it Peaceful, Powerful or Joyful? If they want to, they can then look further out on the wheel to refine their language. Breaking the question down into these three steps makes it less overwhelming. This is something that they can then use with their partners at home.

In other situations I won’t use the wheel, instead, I will offer them options of feeling words based on A) my knowledge of them and B) on my experience of others and C) my own life experience. In response to the “I don’t know” I will say something like – “In my experience, people in a situation like this might feel angry or hurt or overwhelmed” OR “If I was in your shoes I think I would feel anxious or unimportant or maybe angry” and then continue with “Do you think one or more of those feelings might be going on for you?”. If your client is not completely blank, you also have the option to say – “To me, you look like you are irritated or frustrated – would that be about right?

Using these kinds of strategies repeatedly I find that, over time, many clients become more self-aware and articulate. If they can do it in the therapy room, their partners begin to realise they can also expect it at home. There may need to be some discussion about inviting openness, rather than demanding on it (see the discussion of shame and inadequacy above).

Yes, talking in this way leads the client, and we need to be very cautious of clients saying something just to please the therapist. If we choose to guess, we also need to be attuned to subtle signals that our guesses are wrong. However, I would argue that the potential benefits to clients who are inarticulate in this way (and to their partners) outweigh the risk.